Laughing Through The Graveyard: A Guest Post by Jamie Schultz

One of my favorite books is Catch-22,

by Joseph Heller (bear with me for a moment—this has a point

related to fantasy and horror, but it will take me a minute to get

there).

It’s a story about the waning days of World War II, and it

deals with some pretty grim stuff. That’s to be expected, given the

subject matter, but what is surprising is that the book is also

hilarious. It is by turns absurd, sly, clever, and just plain

gut-bustingly funny.

I first read the book when I was eighteen or

nineteen years old, and it was the first time I can remember reading

something so visceral and so dark that was also so damn funny. It

made a hell of an impression.

What I took away from the book is that

Heller had exploited one of the basic truths of human nature—humor is a defense, a weapon, and a fundamentally human reaction to the

grim and the bleak.

It’s used in three ways in the book—first, it adds a human touch to some truly crazy stuff, helping ground the story somewhat. Second, it helps lighten the overall mood. Third, when all humor drops away and Heller delivers the book’s gut punches, they hit that much harder due to the contrast.

It’s used in three ways in the book—first, it adds a human touch to some truly crazy stuff, helping ground the story somewhat. Second, it helps lighten the overall mood. Third, when all humor drops away and Heller delivers the book’s gut punches, they hit that much harder due to the contrast.

These days, I write and read some

pretty dark stuff, ranging from dark fantasy to straight-up horror,

and I’m a little more attuned to the effect of humor on these

things. (It’s one thing to know vaguely how a car works while

you’re driving one, but that knowledge attains an entirely

different importance when you’re trying to put one back together.)

I now regard humor as a vital element of darker work, at least the

really good stuff.

It can work via a couple of different

approaches.

The first mode, camp, actually works in opposition to the horror elements. This is what I’d call the “screw you” mode of horror fiction, where we bundle up our worst fears and straight-up mock them. Don’t get me wrong, campy can be a lot of fun, but it’s also a conscious commentary on the text (if you’ll allow me to be grossly pretentious for a moment), and it’s one that directly winks at the audience. This usually has the effect of pulling me out of a story and allowing me to stand at some kind of ironic remove. It’s the movie and I laughing directly at death.

The first mode, camp, actually works in opposition to the horror elements. This is what I’d call the “screw you” mode of horror fiction, where we bundle up our worst fears and straight-up mock them. Don’t get me wrong, campy can be a lot of fun, but it’s also a conscious commentary on the text (if you’ll allow me to be grossly pretentious for a moment), and it’s one that directly winks at the audience. This usually has the effect of pulling me out of a story and allowing me to stand at some kind of ironic remove. It’s the movie and I laughing directly at death.

You don’t have to look far to find a

lot of examples of camp in horror flicks.

Drag Me To Hell is one (terrible, terrible) example, in which the movie’s horror is virtually undone by the constant winking at the camera.

Maybe a better example is Nightmare on Elm Street. The original film seemed, to me, to revolve around an absolutely terrifying premise—the vengeful spirit that kills you in your dreams. As somebody who has suffered with bad dreams my entire life, this hits home for me, and some of the movie’s more surreal bits are truly chilling.

The humor is a kind of terrifying, cat-and-mouse sadism, but it works. Later films reduce the character to a cheesy one-liner generator and try to up the absurdity factor of each subsequent slaughter. The movies wink at us, and it blunts the horror. I think that’s part of the intent—we’re all gonna die, so making light of it is one way to cope.

Drag Me To Hell is one (terrible, terrible) example, in which the movie’s horror is virtually undone by the constant winking at the camera.

Maybe a better example is Nightmare on Elm Street. The original film seemed, to me, to revolve around an absolutely terrifying premise—the vengeful spirit that kills you in your dreams. As somebody who has suffered with bad dreams my entire life, this hits home for me, and some of the movie’s more surreal bits are truly chilling.

The humor is a kind of terrifying, cat-and-mouse sadism, but it works. Later films reduce the character to a cheesy one-liner generator and try to up the absurdity factor of each subsequent slaughter. The movies wink at us, and it blunts the horror. I think that’s part of the intent—we’re all gonna die, so making light of it is one way to cope.

A related approach goes beyond camp and

straight-up hangs a lampshade on the material. Again, this pushes the

dial over toward “funny” from “scary,” and the two end up

playing a sort of zero-sum game rather than working together.

A great example of this is the Buffy the Vampire Slayer movie—I still crack up at the bad guy’s protracted, ridiculous death throes, but it ain’t scary.

Another example would be the rather absurd movie Idle Hands. There’s this ridiculous bit where two stoners come back as zombies, and when asked why they didn’t go toward the white light when they were killed, one of them says, “Dude, it was, like… really far.” My friends and I quote that to this day—but it ain’t scary. That’s the point.

A great example of this is the Buffy the Vampire Slayer movie—I still crack up at the bad guy’s protracted, ridiculous death throes, but it ain’t scary.

Another example would be the rather absurd movie Idle Hands. There’s this ridiculous bit where two stoners come back as zombies, and when asked why they didn’t go toward the white light when they were killed, one of them says, “Dude, it was, like… really far.” My friends and I quote that to this day—but it ain’t scary. That’s the point.

The other main avenue is using humor

“in the story,” using character interactions or musings to

heighten the horror entirely within the framework established by the

narrative.

One that sticks out in my mind as being particularly clever is in Stephen King’s Rose Madder. Norman, the crazed cop and abusive husband, is musing on his situation as he plans to hunt down his wife, and we get a window into his thoughts.

An excerpt:

At first glance, the image is just so damn funny you have to laugh—but if you give it more than a moment’s thought you stop, uneasy. We’re in Psycho Norman’s head here, and we’ve just watched Norman place responsibility for his actions into some nonexistent third party and clearly state that he has no control over them. That’s terrifying.

One that sticks out in my mind as being particularly clever is in Stephen King’s Rose Madder. Norman, the crazed cop and abusive husband, is musing on his situation as he plans to hunt down his wife, and we get a window into his thoughts.

An excerpt:

“The plumbing between his legs had gotten him into a lot of trouble over the years[…] For twelve years you didn’t notice it, and for the next fifty—or even sixty—it dragged you around behind it like some raving baldheaded Tasmanian Devil.”

At first glance, the image is just so damn funny you have to laugh—but if you give it more than a moment’s thought you stop, uneasy. We’re in Psycho Norman’s head here, and we’ve just watched Norman place responsibility for his actions into some nonexistent third party and clearly state that he has no control over them. That’s terrifying.

Nervous jokes in the face of

frightening, morbid, or just plain grim scenarios are another way

characters contribute to humor “in the story.” Often in urban

fantasy of a darker bent, that comes in the form of a wisecracking,

cynical first person narrator—which itself is pilfered directly

from old hardboiled detective fiction as pioneered by Raymond Chandler.

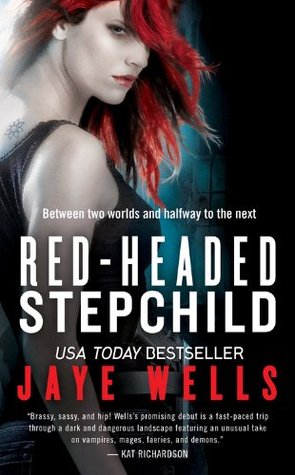

Chandler knew what he was doing. The smartassery humanizes the character, and helps us empathize with them even though they’re probably about to get involved in some pretty grim shit. A great example of this comes from the very first line of Jaye Wells’s book Red-Headed Stepchild:

Chandler knew what he was doing. The smartassery humanizes the character, and helps us empathize with them even though they’re probably about to get involved in some pretty grim shit. A great example of this comes from the very first line of Jaye Wells’s book Red-Headed Stepchild:

“Digging graves is hell on a manicure[…]”

Any discussion,

however brief, of humor in horror would be remiss in not mentioning

what I consider the most masterful, messed-up example of the

kind—David Wong’s deranged masterpiece, John Dies at the End.

This novel somehow manages to play in both worlds—there’s a generous amount of campy silliness, but the main humor of the story consists of nervous wisecracking and character humor against some pretty bleak, existential terror, a sort of spitting in the eye of a twisted mutant offshoot of Lovecraftian horror. This is a book in which a man uses a bratwurst as a telephone and the group of heroes dresses up like Elton John’s backing band in preparation for a climactic scene which is so bizarre I can’t begin to describe it in a single paragraph.

Yet somehow, in the midst of all the craziness, when Wong suddenly plays it straight, it packs a surprisingly emotional wallop. If you’ve read the book, then the paragraph that starts with “Let me tell you everything you need to know about John…” probably sticks out in your memory. There’s a sudden, complete absence of bullshit, and the sincerity bleeds through the page. It’s kind of an awesome trick, if you can pull it off.

This novel somehow manages to play in both worlds—there’s a generous amount of campy silliness, but the main humor of the story consists of nervous wisecracking and character humor against some pretty bleak, existential terror, a sort of spitting in the eye of a twisted mutant offshoot of Lovecraftian horror. This is a book in which a man uses a bratwurst as a telephone and the group of heroes dresses up like Elton John’s backing band in preparation for a climactic scene which is so bizarre I can’t begin to describe it in a single paragraph.

Yet somehow, in the midst of all the craziness, when Wong suddenly plays it straight, it packs a surprisingly emotional wallop. If you’ve read the book, then the paragraph that starts with “Let me tell you everything you need to know about John…” probably sticks out in your memory. There’s a sudden, complete absence of bullshit, and the sincerity bleeds through the page. It’s kind of an awesome trick, if you can pull it off.

In my own writing, however dark it

gets, I find that humor is an absolute necessity. I tend to veer away

from camp for a couple of reasons. First, it’s hard to do well,

believe it or not. “Campy” is an odd hybrid of funny and

terrible, and if the funny misses by even a little bit, it just

leaves you with terrible. It’s a ledge that’s easy to fall off.

Secondly, I don’t want to undermine the dark aspects, but I do want

to humanize the characters and increase the contrast. A lot of the

time I focus on damaged characters in tough situations, and while

that’s not a recipe for nonstop laughter, it would feel almost

alien to me without the sort of gallows humor or wry observations

that people are prone to, even in the worst of spots.

Humor, after all, is a coping mechanism

as much as anything else—and as such, its marriage to horror and

dark fantasy is a lot more appropriate than might be obvious at first

glance. In fact, I believe it’s essential.

K.: Thank you, Jamie, for such an amazing, thought-provoking post!

K.: Thank you, Jamie, for such an amazing, thought-provoking post!

Jamie Schultz has worked as a rocket engine test engineer, an

environmental consultant, a technical writer, and a construction worker,

among other things. He lives in Dallas, Texas.

Find Jamie:

Summary

TWO MILLION DOLLARS...

It’s the kind of score Karyn Ames has always dreamed of—enough to set her crew up pretty well and, more important, enough to keep her safely stocked on a very rare, very expensive black market drug. Without it, Karyn hallucinates slices of the future until they totally overwhelm her, leaving her unable to distinguish the present from the mess of certainties and possibilities yet to come.

The client behind the heist is Enoch Sobell, a notorious crime lord with a reputation for being ruthless and exacting—and a purported practitioner of dark magic. Sobell is almost certainly condemned to Hell for a magically extended lifetime full of shady dealings. Once you’re in business with him, there’s no backing out.

Karyn and her associates are used to the supernatural and the occult, but their target is more than just the usual family heirloom or cursed necklace. It’s a piece of something larger. Something sinister.

Karyn’s crew, and even Sobell himself, are about to find out just how powerful it is… and how powerful it may yet become.

It’s the kind of score Karyn Ames has always dreamed of—enough to set her crew up pretty well and, more important, enough to keep her safely stocked on a very rare, very expensive black market drug. Without it, Karyn hallucinates slices of the future until they totally overwhelm her, leaving her unable to distinguish the present from the mess of certainties and possibilities yet to come.

The client behind the heist is Enoch Sobell, a notorious crime lord with a reputation for being ruthless and exacting—and a purported practitioner of dark magic. Sobell is almost certainly condemned to Hell for a magically extended lifetime full of shady dealings. Once you’re in business with him, there’s no backing out.

Karyn and her associates are used to the supernatural and the occult, but their target is more than just the usual family heirloom or cursed necklace. It’s a piece of something larger. Something sinister.

Karyn’s crew, and even Sobell himself, are about to find out just how powerful it is… and how powerful it may yet become.